Mutang Urud

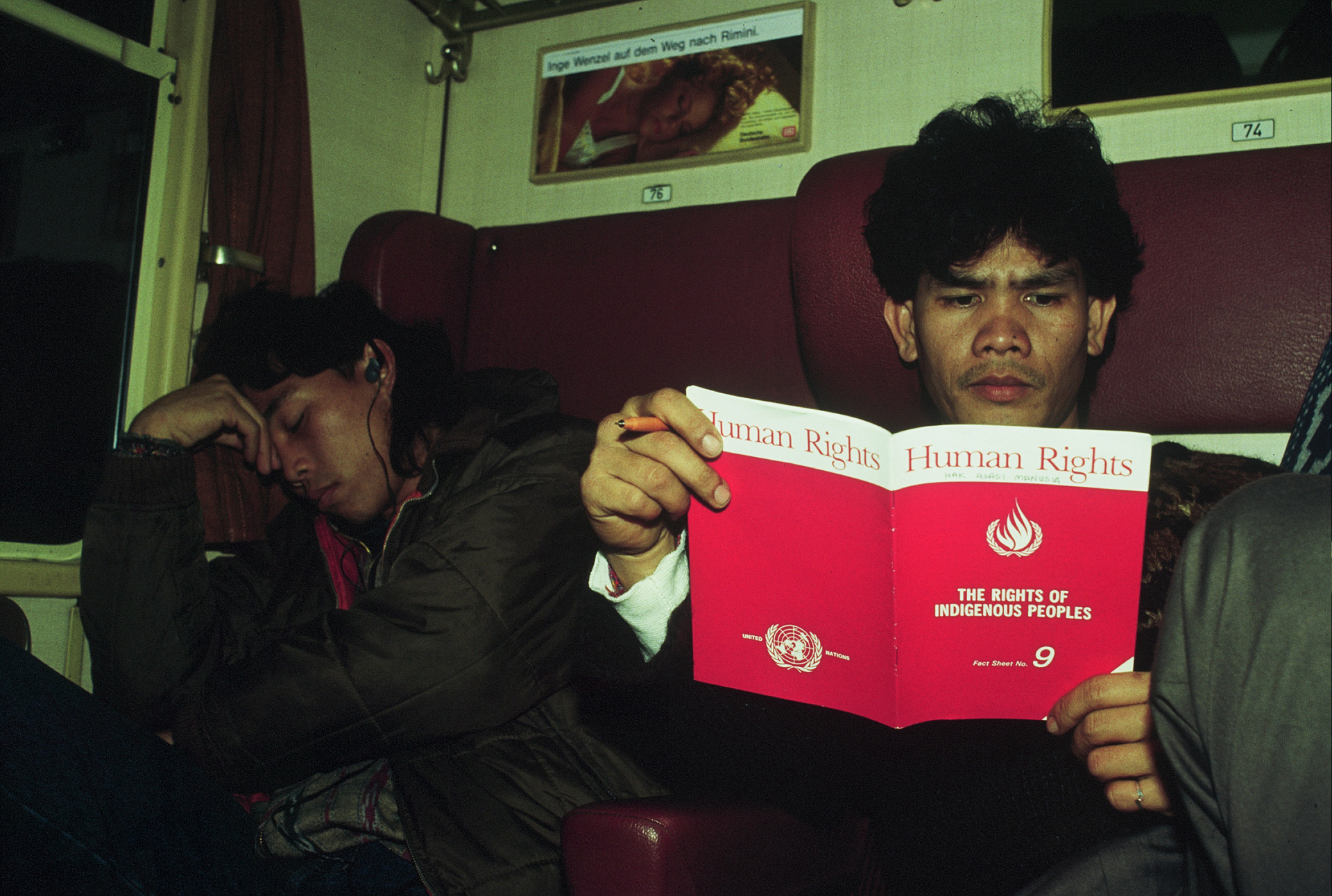

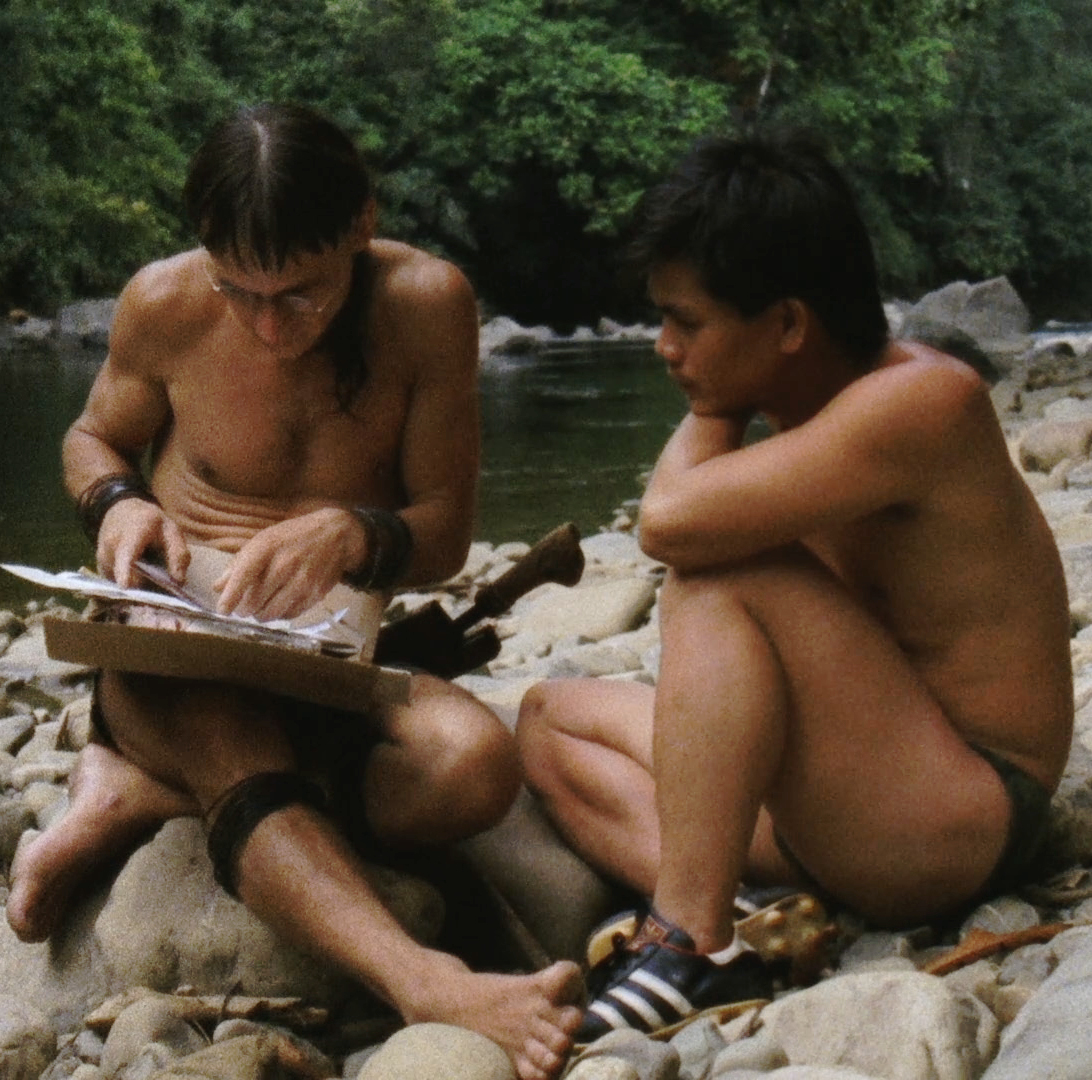

Twenty years have passed since Mutang Urud fled from Sarawak. Together with his friend Bruno Manser he had been organizing blockades in North Eastern Borneo to help the Penan, the Iban and the Kelabit tribes fight the illegal encroachment of their lands by the logging companies.

A member of the Kelabit tribe, he developed a deep relationship with Bruno. It was a relationship that was to change his life. Together with Bruno and Penan leaders Mutang Tu’o and Unga Paren he made a world tour whereby they visited over 25 cities on 4 continents speaking in front of huge crowds. There was a sense of optimism as an upsurge in belief that things had to be done about the state of the planet took hold.

Together the group traveled to Rio for the 1st Earth Summit. Mutang met with Al Gore, whilst Bruno staged a daring parachute jump. Later Mutang addressed the General Assembly of the United Nations. However no change took place in Sarawak. Later Mutang was arrested by the Government and placed into solitary confinement and deprived of food and water. Released on bail he was smuggled over the border into neighboring Brunei. Mutang fled to Vancouver where he lived in the cellar of anthropologist Ian MacKenzie for three years. When we follow him back to Borneo he has spent 20 year in forced exile.

Foreword By Mutang Urud to Lukas Straumanns

Money Logging

I was born in a village in the “Heart of Borneo” as Tom Harrison wrote, near the remote headwaters of the Limbang River, in the Malaysian state of Sarawak. There is nothing more beautiful than the rainforests of Borneo where I spent my childhood. It was both our playground and our sweets shop. We foraged for rinuan honey and ground fruits on the forest floor, and climbed up vines and fruit trees to feed our sugar-starved young souls. Growing up surrounded by mountains, the forest was our only world, and under the dark canopy where the noonday seems like dusk, only the calls of birds and cicadas told us the time of day. Borneo’s virgin forest is also home to tens of thousand of insects, hundreds of bird species, and many mammals that are found nowhere else. A single hectare of our forest supports more tree species than all of Europe.

As a young adult in the 1970s, I watched the loggers not only destroy the forest, but divide communities with corrupting bribes and payoffs. They were like thieves in the night; indeed, they were working in such haste that their machinery could be heard at midnight, even on Sunday. Our ancestral land has been desecrated, our history erased, the very memory of our origins lost. As a young idealist, I could not stand by while this crime was occurring.

In the late 1980s I helped organise blockades to stop the bulldozers and chainsaws. I founded the Sarawak Indigenous Peoples’ Alliance as a rallying point for our peoples’ resistance. Only reluctantly did I travel to twenty-five cities in thirteen countries to tell the world what was happening to our homeland. Back in Sarawak, police attacked our blockades and sent many people to jail. I was arrested, interrogated, and held in solitary confinement. Upon my release, I left Malaysia to speak about these environmental crimes at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. In 1992, I addressed the United Nations General Assembly in New York in support of land rights for Indigenous Peoples. Unable to return home, I studied anthropology in Canada in order to acquire new skills that would help me save some of what was being lost.

Fearing arrest, for twenty years I dared not return to my homeland. When I finally did, I found that the ecological crimes had only increased. The forest I had loved was almost gone. Rainforests that had been the home of human beings for at least 40,000 years had been destroyed in little more than thirty. At least 80% of Sarawak’s ancient forest is now gone. Only 11% of the primary growth remains. How did it disappear?

I applaud my dear colleague Lukas Straumann for his diligence and investigative skill. His research exposes the wanton greed that has fuelled the destruction of the place I call home.

This book investigates two crimes. The first is how a small group of very rich politicians and businessmen could destroy the richest ecosystem on earth despite not owning it, despite local and global outcry, despite international laws and regulations. Simply put: Who has stolen our trees?

This book investigates two crimes. The first is how a small group of very rich politicians and businessmen could destroy the richest ecosystem on earth despite not owning it, despite local and global outcry, despite international laws and regulations. Simply put: Who has stolen our trees?

The second crime is more subtle. Surely, if my people have lost their ecosystem, their traditional way of life, their clean drinking water, and their freedom to roam the forests, they must have gained something. Yet they haven’t. Many of the people of Sarawak are as poor as they were when I was born. And yet, the value of the trees that have been felled is estimated to exceed US$ 50billion. This profit has fed corruption, kept oligarchs in power, been used to commit further crimes. Fortunes have moved through the world’s financial system, mostly secretly, to places as distant as Zurich, London, Sydney, San Francisco and Ottawa.

Lukas Straumann shows how this, one of the greatest environmental crimes in history, is much bigger than just the theft of trees. It is also about power, more precisely, how a corrupt autocrat has liquidated a forest in order to keep himself at the helm of a state. For my people it is also more than a question of trees. It is about our culture they have stolen.

This book should be essential reading for anyone who uses a bank, buys property, or invests in the stock market. Only by understanding how a rainforest can be converted into a building as far away as the FBI headquarters in Seattle, can we hope to stop the kind of corruption that threatens the world’s natural places, and the people for whom these are home.

Mutang Urud

Montreal, Canada

July 2014